"aus LICHT will be thé musical theatre event of 2019" - NRC Handelsblad

This article was printed in the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad on 2 January 2019

Fifteen hours of experimental theatre: Immerse yourself in Stockhausen's aus LICHT - Seven questions about Stockhausen

The National Opera, Holland Festival and the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague have joined forces to perform Karlheinz Stockhausen’s aus Licht, the most ambitious opera ever written. The performance of all seven parts from 31 May to 10 June will be a historic and internationally never-before-seen spectacle. Here is a brief introduction to Stockhausen in seven questions.

1 Fifteen hours of experimental musical theatre by Avant Garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. It seems too good to be true. Should we be pleased?

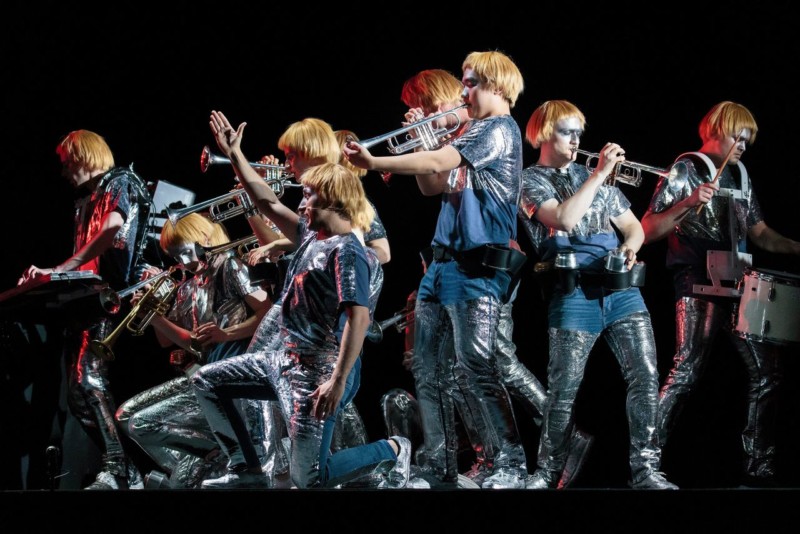

Are you a fan of Gesamtkunst which combines a variety of art forms (singing, instrumental music, theatre, dance, light, colour)? Are you prepared to open your mind to a brand new and megalomaniac universe in which string quarters fly through the air in helicopters (Stockhausen was obsessed with flying, birds and aeroplanes) and angel choirs sing seven languages in procession?

Then you definitely have something to get excited about. Yet when Director Pierre Audi announced a series of performances with fragments from Stockhausen’s opera heptalogy LICHT (i.e. seven-parts, just like Harry Potter) would be the swansong of his thirty years at the helm of The Dutch National Opera (DNO), there was an uproar. An internet petition against aus LICHT amassed 52 signatures. ‘A daft venture’, someone wrote. Someone else described it as ‘a monstrous project for the happy few’. A third person said, ‘Stockhausen was a fascist.’

2 Was Karlheinz Stockhausen really a fascist?

No. But he was a monomaniac perfectionist who lived for and through his music. The specific criticism harks back to an explosive remark about the attacks on the Twin Towers on September 11th, which Stockhausen described as ‘the greatest work of art’. He retracted his comment on the same day; of course he thought the attacks were also ‘a crime’. Seen through his artist’s eyes, he was astounded by the years of planning that went into the attacks: a true ‘devil’s composition’. However, the damage had already been done. Concerts were cancelled. His daughter Majella rejected the name Stockhausen as if it were contaminated.

To try and put what he meant into context: Stockhausen (1928 – 2007) was a teenager during the Second World War. His mentally-ill mother was murdered in 1941 as part of the Nazi’s euthanasia project (Life unworthy of life). His father, a teacher, died at the Eastern Front. Stockhausen was orphaned at sixteen. He saw the sky above his homeland, the undulating Bergisches Land mountain range to the east of Keulen, where he would later live for the rest of his life, lit up by anti-aircraft guns, phosphorus bombs and crashing planes: a terrifying, yet also gruesomely stunning, sight to see. According to experts, Stockhausen's diverse but consistent spiritual oeuvre can be summed up as a lifelong attempt to find an answer to his childhood trauma. Stockhausen's second of four wives, the artist Mary Baumeister, described it this way in her autobiographical page turner ‘I am hanging in the triplet lattice: My life with Karlheinz Stockhausen’: ‘The basis of Stockhausen’s music is pain, the remedy is love.’

3 Why did Stockhausen devote 25 years of his life to LICHT and why does it need to be so elaborate?

Stockhausen composed the wildest opera in the history of mankind with LICHT. The original inspiration came from Kyoto in 1977. Monks singing awakened Stockhausen to the realisation that all varieties of world music originated from the same source; although they differed, they are all essentially related. This is where the idea to compose seven operas with a single united message over 25 years came from.

LICHT has never been performed in full, so no-one (as yet) can witness the full force of a complete immersion. According to the clarinettist and composer’s widow Suzanne Stephens, ‘many vital scenes’ are missing from the fifteen-hour event in June in the Gashouder venue in Amsterdam (in one location, although Stockhausen actually dreamt of seven special theatres). However, the Amsterdam aus LICHT trilogy is the first ever ‘comprehensive’ scenic performance of this opera.

4 Is there a narrative in the seven operas?

Each opera is named after a day of the week, which are represented by colours, scents and symbols. There is some kind sort of plot connecting the three archetypal protagonists Michael, Eva and Lucifer (with accompanying instrumentalists on the stage and dancers). This plot is only the surface of many underlying layers of meaning. Ultimately, you experience the scenes more as a dreamy, modular sequence, where some events definitely reflect back on Stockhausen’s childhood memories.

Do you need to understand all this? No. You need to experience aus LICHT for yourself. Leave your sceptical questions about meaning and nonsense behind and surrender yourself to the music and theatre that is ‘raising everything to a different and higher plane’, according to the aus LICHT website. To then leave the theatre with refreshed belief in the power and necessity of active human connection and in love as the answer to imperfection. When people are able to turn negative experiences into the power to overcome mutual differences, they can work together and create a more harmonious world. Belief, hope and love are inscribed on Stockhausen's gravestone.

5 Amen! Is that all that can be said?

That's too simple. Stockhausen was baptised as a Roman Catholic when he was a child. Christian roots can be seen throughout aus LICHT. Even Stockhausen himself regarded the ‘spiritual religion’ as his guiding principle. However, he had a broad spiritual outlook: Eastern religions and the mystical The Urantia Book (1955), ‘passed on’ from the beyond, were influential.

Crazy or genius? A bit of both presumably. The music isn’t 29 hours of ingenuity, but fragments certainly are. The sensuality and urgency of the music are unmistakeable throughout the pieces.

6 The musical direction of aus LICHT is controlled by Stockhausen's last widow, Kathinka Pasveer. How come?

Stockhausen was an ultra-perfectionist. If anything went wrong, he suffered from stomach ache. That is why he wrote everything down in bulky scores and played an active role in the many performances of his music. There is free rein over adding lighting and staging, which will soon be created in Amsterdam by lighting designer, Urs Schönebaum. At the last moment, Director Pierre Audi will add even more atmosphere with his mis en espace.

Otherwise Stockhausen's scores already start with pages of instructions: how the loudspeakers should stand, how you assemble the drums you need, how the dynamics need to be and how you sing a certain phrase (such as the German phrase ‘mit etwas offenen, lockeren Lippen’). Even the choreography for the singers is written in the notes.

Pasveer, who collaborated intensely with Stockhausen for many years, now supervises the rehearsals for aus LICHT ‘stricter than the pope himself’. The aim: hundred percent precision in every parameter. The musicians involved, which includes a number of students on the specially designed aus LICHT Master’s programme at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague, appreciate that. ‘You feel it when you do exactly what it says,’ they say. Almost like an image coming into focus. Although it might seem contradictory, the precision can be highly emotive.

The role of electronica in the opera is also interesting. ‘It’s my job to adapt to the technology available in my time,’ said Stockhausen – a pioneer of electronic music. Strangely enough, his legacy now preserves a frozen ideal, as some of the equipment Stockhausen used at the time is no longer available. That’s why the contemporary sound guys for aus LICHT sometimes sneak in the latest gadgets.

7 What would Stockhausen have thought of all this?

Don't rule out a cheeky smile. Stockhausen wasn’t averse to humour and relativity. ‘My life's work is just a tiny part of the development of music,’ he once said, even though he fervently believed in the salvation of his own music.

Karlheinz Stockhausen was buried on Thursday 13 December 2007 in the woodland cemetery in his hometown of Kürten, where his widows still live and work tirelessly for the Stockhausen Foundation for Music. They also followed every last instruction he left for the funeral from ordering specially made blue tiles for his tomb, getting the enormous steel disc for his grave engraved and providing the (fragrant) plants next to it. They only chose his jumper, which was his Sunday jumper, a white one with golden threads; the widows thought it was the nicest. They had to laugh about the fact it was his Sunday jumper, rather than his Thursday jumper. ‘He might well have been angry about that.’